Host shifts, Reproductive Isolation, and Speciation

One of the primary motivating questions in our research group is: for parasitic insects, what is the relationship between host use, the evolution of reproductive isolation, and the origin of species? Host diversity is strongly correlated with the species diversity of many parasitic insect groups. This has led to the hypothesis that insects speciation may often be an outcome of their shifts to new hosts. However, because today's diversity is a product of past events (and therefore are obscured by time), it is not clear whether host shifts cause the evolution of the initial reproductuve isolating barriers between different host-associated populations, or if shifts occur primarily after populations have aready begun to diverge (barriers predate the host shift). Many of our study systems are chosen because we think they might allow us to chip away at these questions. We have also reviewed the extend to which other insect systems can address this question: Forbes AA, Devine SN, Hippee AC, Tvedte ES, Ward AKJ, Widmayer HA, Wilson CJ. 2017. Revisiting the particular role of host shifts in initiating insect speciation. Evolution 71:1126-1137. link

We haphazardly maintain a wiki page that collects and evaluates studies dealing with the relationships between insect host use, reproductive isolation, and speciation. This dataset is an outgrowth of the Evolution paper named above. The wiki-dataset can be found here: https://wiki.uiowa.edu/display/InsectHostShifts/Insect+Host+Shifts+and+Speciation) and anyone is invited to collaborate on its maintenance or by sending us papers that describe relvant systems.

Estimating the relative richness of animal life

The lab has also become interested in how to improve estimates of relative animal diversity. Because we focus on parasitic insects, we wondered about the strength of the common assertion that beetles (insect order Coleoptera) are the most species rich group of animals. There are certainly many beetles, and they are far and away the order of animals with the largest number of named species. However, more time and effort has been applied to this charasmatic group than to other orders, suggesting the possibility for various biases. In a 2018 paper ("Quantifying the unquantifiable: why Hymenoptera, not Coleoptera, is the most speciose animal order") we provide a model alongside data that together suggest that the Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, and sawflies) are the larger animal order.

In collaboration with the Wiens Lab (U. Arizona) and the Bagley Lab (THE Ohio State University - Lima; est. 2020), we are now thinking about how to extend these approaches toward estimating relative global diversity of other animal groups (and beyond).

Hidden niches and tropical insect diversity across three trophic levels

We are collaborating with Marty Condon at Cornell College, Brian Wiegmann at NC State, Gaelen Burke at U. Georgia, Sonja Scheffer at USDA-ARS, and Nina Theis at Elms College to understand patterns of extreme diversity among neotropical flies and parasitoid wasps. Blepharoneura flies are morphologically cryptic, highly diverse, and highly host-specific, yet many species overlap in the same host plant niche. Likewise, their Bellopius parasitoid wasps are also speciose, cryptic, and host specific (to both flies and plants). We are using molecular markers, natural history collections, and patterns of lethal interactions between flies and wasps to ask what explains patterns of diversity in both trophic levels. An NSF Dimensions of Biodiversity grant currently supports this research. Our recent published work on this topic includes:

Winkler IS, Scheffer SJ, Lewis MJ, Ottens KJ, Rasmussen AP, Gomes-Costa GA, Santialln LMH, Condon MA, Forbes AA. 2018. Anatomy of a neotropical insect radiation. BMC Evolutionary Biology. Online Early: link

Ottens K, Winkler IS, Lewis ML, Scheffer SJ, Gomes-Costa GA, Condon MA, Forbes AA. 2017. Genetic differentiation associated with host plants and geography among six widespread species of South American Blepharoneura fruit flies (Tephritidae). Journal of Evolutionary Biology 30:696-710. link

Condon MA, Scheffer S.J., Lewis M., Wharton R.A., Adams D.C., Forbes AA. 2014. Lethal interactions between parasites and prey increase niche diversity in a tropical community. Science. 343:1240-1244. link

Media: National Geographic, Popular Mechanics, I F-ing Love Science,

Diversity and Evolution among diverse communities of gall wasp natural enemies

As part of a consortium with several other labs, we are interested in how the diverse communities of insects that parasitise gall-working oak wasps have evolved. This work is wide-ranging, and still in its incipient stages, but currently involves the characterization of diversity both in specific gall systems as well as on a continental scale. We have begun to publish in this area, and our recent papers are below:

Weinersmith KL, Liu S, Forbes AA, Egan SP. Tales from the crypt: a parasitoid manipulates the behavior of its parasite host. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B 284:20162365 link

Media: National Geographic, Science, Popular Science, The Atlantic, Gizmodo, New Scientist, CBS News, The Scientist, BBC World Service, San Francisco Chronicle, Faculty of 1000 Recommended, Discover Magazine's Top 100 Science Stories of 2017

Egan SP, Weinersmith KL, Liu S, Ridenbaugh RD, Zhang YM, Forbes AA. 2017. Description of a new species of Euderus Haliday from the southeastern United States (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea, Eulophidae): the crypt-keeper wasp. Zookeys 645:37-49. Link.

Media: Daily Mail

Forbes AA, Hood G R, Hall M.C., Lund J., Izen R., Egan SP, Ott J.R. 2016. Parasitoids, hyperparasitoids, and inquilines associated with the sexual and asexual generations of the gall former, Belonocnema treatae (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae). The Annals of the Entomological Society of America 109:49-63. link

Genome evolution and adaptation in an asexual insect species

In a collaboration with John Logsdon (University of Iowa), we are studying patterns of genomic evolution in Diachasma muliebre, an asexual Braconid wasp found in the Northwestern United States. Females of this wasp lay diploid eggs which develop into females and do not make males. Our work so far (Forbes et al. 2013) suggests that all present-day lineages have evolved from a single ancestral wasp, and that lineages have since diverged phenotypically, now inhabiting significantly different slices of the species's overall temporal niche. Current work investigates rates of molecular evolution across genus Diachasma, with a focus on changes that may occcur across a transition to aexuality. Our recent published work on this topic includes:

Tvedte ES, Forbes AA, Logsdon Jr, JL. 2017. Retention of core meiotic genes across diverse Hymenoptera. Journal of Heredity. 108:791-806. link

Forbes AA, Rice LA, Stewart NB, Yee WL, Neiman M. 2013. Niche differentiation and colonization of a novel environment by an asexual parasitic wasp. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 26:1330-1340.

The origin and evolution of reproductive barriers in Strauzia (sunflower maggot) flies

Flies in genus Strauzia span the so-called "speciation continuum" from long-diverged species to more closely related species, to lineages that continue to experience gene flow. As with many specialist phytophagous insects, their host associations and phylogeny suggest that divergent ecological selection has played a role in their speciation. Our lab is using this system to study the origin and evolution of different reproductive barriers across the continuum of ecological speciation. We are also working on assembling a robust phylogeny for the genus, relating morphological variation to genetic variation among closely related lineages, and trying to understand the phylogeographic history of these flies in the context of the historical distribution of their host plants.Our recent published work on this topic includes:

Hippee AH, Beer MA, Bagley RK, Condon MA, Kitchen A, Lisowski EA, Norrbom AL, Forbes AA. 2020. Host shifting and host sharing in a genus of specialist flies diversifying alongside their sunflower hosts. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 34:364-379. link.

Hippee AC, Elnes ME, Armenta JS, Condon MA, Forbes AA. 2016. Divergence before the host shift? Prezygotic reproductive isolation among three varieties of a specialist fly on a single host plant. Ecological Entomology 41:389-399.

Forbes AA, Kelly PH, Middleton KA, Condon MA. 2013. Genetically differentiated races and speciation-with-gene-flow in the sunflower maggot, Strauzia longipennis. Evolutionary Ecology. 27:1017-1032.

We highlighted some of our recent and ongoing Strauzia work in a talk to the Entomological Society of Washington in 2021 (starts at the 13:00 mark): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nCeFeTHLgs0

Parasitoids of Rhagoletis flies - Cascades of Speciation?

The apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomonella, is one of the best-known examples of ecological speciation in action. Over the last 400 years, populations of this native North American fly have moved from their native hosts, fruits of hawthorn trees (Crataegus) into introduced European apples. These two populations, though not isolated by geographic barriers, nevertheless appear to have formed incipient species in just this short period of time.

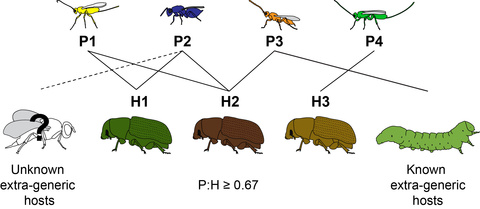

Diachasma alloeum (figure at right) is a parasitoid wasp that lays its eggs in the developing larvae of R. pomonella. Wasps in this genus attack several different Rhagoletis fly species, including those that infest apples, hawthorns, blueberries and snowberries. We asked the following question: has the divergence of these wasps' fly hosts driven a sequential, or "cascading" host race formation in D. alloeum? Several pieces of evidence suggest that the answer is yes: First, eclosion of wasps in each host-associated population closely tracks eclosion of their respective fly hosts, meaning that the wasps are at least partially allochronically isolated from one another. Second, the two populations of wasps respond differently to fruit odors: they prefer their natal fruit odor and (in some tend to avoid nonnatal odors. Third, significant microsatellite allele frequency differences define host-associated populations (Forbes et al. 2009).

With funding from the National Science Foundation (DEB-1145666), we asked whether other egg and larval parasitoids of Rhagoletis are also undergoing host-associated divergence. A second larval parasitoid (Diachasmimorpha mellea) and an egg parasitoid (Utetes canaliculatus) are also commonly found attacking the new apple race of R. pomonella. Our research (Hood et al. 2015) showed that these parasitoids are also forming new species (a 'starburst' of speciation). This project was a collaboration between the Forbes lab and researchers at the University of Notre Dame (Jeff Feder and Glen Hood) and Cornell University (Charlie Linn). The data collection for this work is mostly finished, but some exciting papers are still to come. Our recent published work on this system includes:

Hamerlinck G, Hulbert D, Hood GR, Smith JJ, Forbes AA. 2016. Histories of host shifts and cospeciation among free-living parasitoids of Rhagoletis flies. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 29:1766-1779

Hamerlinck G, Lemoine NP, Hood G R, Abbott KC, Forbes AA. 2016. Meek mothers with powerful daughters: effects of novel host environments and small trait differences on parasitoid competition. Oikos. 125: 1516-1527.

Hood GR, Forbes AA, Powell THQ, Egan SP, Hamerlinck G, Smith JJ, Feder JL. 2015. Sequential Divergence and the Multiplicative Origin of Community Diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A. 112:E5980–E5989.